ABOVE: Paul Revere Williams was a Black architect who began designing homes and commercial buildings in the early 1920s. He was the first Black architect to become a member of the American Institute of Architects in 1923.

Students at Hillcrest High School in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, are learning a hard and valuable lesson. These students are not just hearing about the fight behind the civil rights movement, they are living it. In the same spirit behind the boycotts, marches, and lunch counter sit-ins of the 1960s, more than 200 Hillcrest students recently walked out of class to protest a school administrator’s decision to limit a student-led Black History Month program. The students said they were told to leave out significant historical moments, including slavery and the civil rights movement, from the upcoming program.

They “couldn’t talk about slavery and civil rights because one of our administrators felt uncomfortable,” said one student involved in the protest.

While the walkout lasted almost an hour, the confusion, hurt, and anger can be long-lasting. The feeling of disrespect is painful, but the students’ response with an organized and peaceful demonstration is admirable. These students became living examples of the Black experience from America’s past. They now know—if they didn’t before—that the subjects of slavery and the civil rights movement are not popular with certain individuals. It makes them “uncomfortable” for a variety of reasons. The students also know that there are issues worth fighting for due to national attempts to limit the truth behind the Black experience from being taught and shared.

The story of slavery, including the positive contributions by enslaved people, can unleash a tremendous amount of pride and inspiration for Black students at Hillcrest and elsewhere.

President Biden recently gave his annual State of the Union speech to the American people before a joint session of Congress. The speech, delivered from the U.S. Capitol—the nation’s signature building as the seat of government—literally would not have been constructed in Washington, D.C., without enslaved labor. Truthfully, slaves didn’t just pick cotton and tobacco, they also built impressive buildings with little or no pay. The authority to construct the Capitol building was granted to the president by Congress in the Residence Act of 1790. This law gave President George Washington broad powers to oversee the construction of a new city on the banks of the Potomac River, complete with the buildings necessary to house the chief executive and the U.S. legislature.

The sparsely populated Maryland countryside created a major problem precisely because the local manpower essential for a project of this magnitude did not exist. There were too few carpenters, bricklayers, plasterers, and roofers. There were virtually no stone cutters or carvers. Architects, engineers, and surveyors had to be brought in from other areas. The only human resource the region could supply in abundance was unskilled labor–slaves.

Even before the Capitol’s design was finalized, the commissioners realized they were facing a long-term labor shortage. Rented slave labor from the surrounding slave states of Maryland and Virginia was the option most often used.

While records offer few specific details, enslaved people helped in every facet of construction activities for the new Capitol building. Shackled slaves made their way down Pennsylvania Avenue and worked alongside Black and white freemen in carpentry, masonry, carting, rafting, roofing, plastering, glazing, and painting. The one activity which seems to have been performed exclusively by slaves was sawing both wood and sandstone. Skilled slaves were often trained in the art of brickmaking and bricklaying. Of all the work performed by enslaved people, carpentry was the most significant contribution to the construction of the U.S. Capitol.

Carpentry was a useful skill taught to slaves and passed down to succeeding generations. So many enslaved people’s descendants became carpenters and masons as a profession, and a means to support their families. Did any slaves ever imagine that future generations of Blacks would be elected lawmakers and serve in the legislative building built by their hands and hard work?

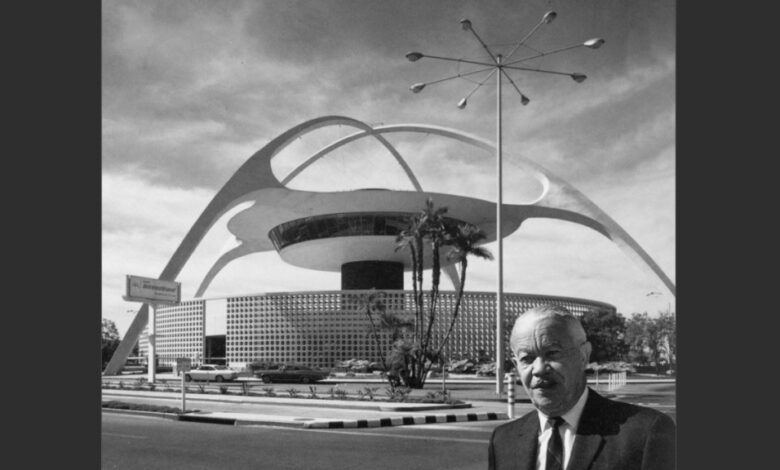

As we built significant buildings, we also designed them. It is not likely that the story of Paul Revere Williams will ever be mentioned as it should. He was a major contributing figure to American architecture despite the racial obstacles.

Paul Revere Williams was a Black architect who began designing homes and commercial buildings in the early 1920s. When he died in 1980, he created approximately 2,500 buildings, mainly in the Los Angeles area. He was the first Black architect to become a member of the American Institute of Architects in 1923. His work signified the glamour of Southern California. The homes designed by Williams possessed grace and elegance that attracted people of wealth and taste. His clients included Frank Sinatra, Lucille Ball, Desi Arnaz, Cary Grant, and Danny Thomas. In later years, Denzel Washington, Ellen DeGeneres, and Andy Garcia all lived in homes designed by Williams. By law, he was not allowed to live in some areas where he designed homes. He was forced to adjust to the hard reality of racism of his day by teaching himself how to draw upside down so white clients would not be uncomfortable sitting next to him. He believed that for every home and commercial building he could not buy or live in, he was opening the doors for the next generation.

Unfortunately, people are “uncomfortable” because Black perseverance and excellence threatens the idea of white supremacy and cannot be stopped.

David W. Marshall is the founder of the faith-based organization TRB: The Reconciled Body, and author of the book God Bless Our Divided America. He can be reached at www.davidwmarshallauthor.com

The post We Built This Country appeared first on Houston Forward Times.